2005-11-xx Keyboard - Depeche Mode

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

Martin Gore and Andrew Fletcher discuss the production of Playing The Angel alongside album producer Ben Hillier in the November 2005 issue of Keyboard magazine. Scans courtesy of Joe Muscara.

Article

DEPECHE MODE

by Steve Fortner

Photo by Robb D. Cohen/Retna

BEHIND THE SCENES - Not content to merely interview the principals involved, Steve Fortner performed some serious journalistic forensic work to bring you this month's cover story on Depeche Mode. After learning that Andrew Fletcher, Martin Gore, and David Gahan tracked Playing the Angel at a studio he himself had worked in, Steve ferreted out the synth-laden studio shots that tell the backstory of analog-heavy masterpiece. He later brought that story to life by tracking down producer Ben Hillier to find out just who was plugged into what in order to realize this sonic delight. All in a day's work, says Steve. Way to go!

A clever introduction has no place here. It would imply that one is needed to begin with, doing no justice to this simple fact: Depeche Mode is the most important synthesizer band on the planet. First to achieve arena-act status, they have reigned as the undisputed overlords of the oscillator during the 25 years since "Just Can't Get Enough" conquered dance floors everywhere. From Detroit techno to deep house to the reso-pulsed rock of today's enfants terribles such as the Killers and the Bravery, their influence has proven inescapable.

That they're truly a synth band bears repeating. Founders Andrew Fletcher, David Gahan, and Martin Gore are all as technologically savvy as it gets, and who can forget the wisdom of Mode alumnus and elder statesman of synthesis Vince Clarke, who famously described the timing of MIDI sequencers as "crap." Their penchant for analog hasn't changed, but more importantly, the three chums from Basildon, Essex, are a more cohesive creative unit than ever on Playing the Angel, their first studio release since 2001's Exciter. Frontman Gahan contributed three tracks, with longtime chief songwriter Gore penning the rest. Where Exciter was pristine and even understated, the new album is, in the words of producer Ben Hillier, known for his work with Blur and The Doves, among others, "painted with very bold strokes. If it gets loud, then it gets loud!"

From the siren-like slap in the face that leads off "A Pain That I'm Used To" (a heavily-processed Yamaha CS-5) to the lush, melodic "Precious", extravagant sonics recall the legendary Violator more than any DM effort since. At the same time, someone who managed never to hear a note of Depeche Mode until now could well take Angel for the debut of an outrageously talented and unashamedly hungry avant-garde trio poised to take over the world.

Martin and Fletch chatted with us in Los Angeles as they prepared for a massive tour beginning this month. Thanks in part to one of the most fiercely devoted fan bases in any genre of music, they're once again filling the likes of Madison Square Garden and the Staples Center.

You began recording Playing the Angel at Sound Design in Santa Barbara, which the studio owner said was the "incubator" for the songs. What was the incubation process like?

Martin Gore: There wasn't songwriting going on in the studio per se, which may be a bit unusual when a band gets together to record.

Andrew Fletcher: It was the incubator in this sense: Martin and Dave came in with demos they'd done individually, and we worked on arrangement, sonics, and general vibe of the tracks. We tried a lot of sounds and made a lot of decisions there.

MG: Sometimes things stick close to the demos, but the majority of the time they take on a whole life of their own when we get together, winding up very different from how they started. Ben [Hillier] also really pushed us, on every track. We could really go off on tangents, but he'd always rein us in. We gave him a lot more control than we've given other producers. This time, we wanted a "headmaster" figure to keep all in check. If he made a decision we didn't agree with initially, we'd try to trust it.

Can you generalize about the direction he took you in?

MG: He's very similar to [Violator producer] Flood, actually, and I'd contrast him most directly with Mark Bell, who did our last record. Ben's worked with so many artists, many of them not "electronic rock" like us, and we weren't aware he was so into electronics. No one knew he'd turn up at the studio with, like, 20 vintage synths, and he was constantly on the Internet looking for new ones.

AF: He's also a bit hyper, literally running around the studio as we worked, patching things like a madman.

MG: We've been around awhile, so it was nice to have that sort of infectious enthusiasm in the room. energized us. One can bear it. The new record is definitely more synth-heavy than Exciter.

AF: Exciter was more somber, and more about digital perfection, with everything in its place. Here, we're certainly using those old synths!

Your studio setup was also unconventional.

MG: There were three different Pro Tools HD rigs, one for each of us. We didn't use the control room as such, just another area for working. Dave sang right from there, and Andy and I occupied the tracking room in one of the booths.

Martin, having written most of the songs over the years, do you typically begin on piano or guitar, or with synths and a computer?

MG: In the past, I've done the former a lot. I've always felt that when you're beginning at the computer, you can get so many interesting sounds and atmospheres going as to fool yourself into thinking you've got a good song. That's been a golden rule of mine, but this time around, I broke it and indeed started out with synths. I just had to be very careful.

Is there a song that stands out as coming together around a particular keyboard sound?

MG: The main [piano] motif that goes throughout 'Precious' was on the demo, and remained intact for the version on the record.

I was struck by the analog bass that bubbles up underneath the intro to '[A] Pain That I'm Used To' as well. It's classic Depeche Mode.

MG: That was one of the most difficult things to get right.

AF: That song did start in Santa Barbara. It went through lots of stages. We were settled on the basic arrangement, the "siren" intro, then pulsating bass, then Dave comes in with the opening line — the rhythm just never seemed to groove properly. Otherwise, this may have been our easiest album to make other than Speak and Spell [the first] which was done in three weeks because we were playing live a lot at the time.

Tons of bands I've spoken to cite you as a major influence. Let's say you encounter a new artist who's copping your vibe. To further their education, what would you have them listen to?

AF: Kraftwerk. There's so much else. See, we were at our most impressionable during the glam and punk rock eras, and that's in our melting pot as much as "electro." It really influenced our values and aesthetic.

How would you describe those values?

AF: The glam aspect is that we like to perform. We like to dress up a bit. [Laughs.] Nothing against bands who play in jeans and a T-shirt, but we've always been intent on giving people a show. Secondly, our reason for starting a band shared the central value of punk — it wasn't solely about technical ability. You needed to have good ideas and an attitude. That's one of the reasons we went on [independent label] Mute Records and shunned the majors. Third, we were inspired by bands like Kraftwerk and very early Human League, because frankly, keyboards are much more interesting than guitars!

Can you say anything about how the revolution in technology over the past 25 years bas affected your music? Has it changed your creative process, or is it more like the same challenges, only on flat screen monitors now?

AF: You could say our career began with the introduction of cheap monophonic synthesizers.

Is that because you found them better suited to conveying the dark emotional themes your music is known to explore?

MG: We found them better suited for conveying to the gigs! [Laughs.] Seriously, think about what it was like for guitarists in the early '80s. You needed different amps for different tones, and a bass player had to have a big rig to be sure of projecting. By contrast, we could simply take four or five suitcase synths, get on the train, and plug into the PA when we arrived at the club.

AF: From there, it was on to early digital keyboards, then Emulators, then Synclaviers. With every album, it was like there was a conscious decision to embrace the cutting-edge technology of the day. We also had an almost-rule never to use the same sound twice. Also, never a guitar, unless it’s so processed it sounds like a keyboard. This went on, oh, up until Violator, when Flood, said “This is just getting too crazy, guys.”

Nonetheless, wasn’t there always a clear intention to present yourself to the world as a “synthesizer band”?

AF: Far more than that. We were on a full-fledged crusade. During the ’80s, we encountered a lot of resistance from the media and the music business in general, and it just made us stick to our guns, because we really saw electronic music as the way forward.

That’s ironic, because today the press sees the '80s as the golden age of electronic pop. New acts get called “retro” because of their use of synths, not to mention a more glam look, unlike the grunge that ruled the '90s. Maybe you’ve won your crusade.

AF: That is ironic. At the time, it felt like what we were doing was alien, but when we began to play America, I think we were the first synth band to be filling large venues. It was quite unusual.

Just as technology has facilitated creating your music, it’s also enabled sharing and downloading, sometimes without paying. What are your views on that?

MG: The record industry has been very lazy for the past ten years or so, which puts a lot of the blame on them. 'Precious' even got leaked. Some guy hacked into the video director's web server and got a blue-screen version of the video with the whole song on it!

AF: It's hard for a band like us, because we have this whole promo schedule with release dates and all, and piracy really screws that up. On the other hand, I have a record label [Toast Hawaii], and my first signed artist [the electronic duo Client], is gaining notoriety precisely because they've been rather open and free about letting people copy and share their tracks. So it's a good and bad thing at the same time.

What was the most pleasant surprise you encountered while making this album?

AF: Getting along reasonably well! [Laughs.]

PRODUCING PLAYING

The DM guys spoke so highly of Ben Hillier’s production that this story wouldn't be complete without his input. As affable as he was encyclopedic about the sessions, he gave us the rundown on Angel’s recording secrets and distinctive synth sounds.

This was your first time working with DM. How did your approach differ from other projects?

For one thing, I've usually produced bands that have live drums and bass, and while I'm quite into synths, they’re normally used for treatments and layers. I didn’t want to have too many live drums per se; I wanted to be true to their legacy by using synths to create the rhythm section itself. The other big difference was analog sequencers. We recorded lots of live passes then took samples of those “performances” as building blocks for songs.

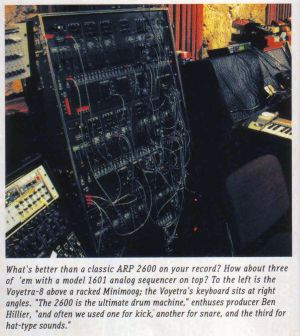

Where can we hear obvious examples of the three ARP 2600s at work?

The drum sounds on "I Want It All" [one of Gahan’s songs] are those, run from the 1601 as we played with the envelopes and filters. Then, there’s that rather ominous bass that begins "The Sinner In Me", which also uses the 2600s. "John The Revelator" has these high, randomish arpeggios at the beginning and end. That was a VCS-3 simulated by [Native Instruments] Reaktor, combined with this cool ring mod Martin cooked up on his Nord Lead 2. Other software that saw a lot of use included their Pro-53 and [Way Out Ware] TimewARP 2600.

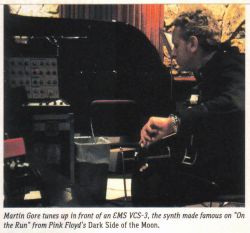

I saw a real VCS-3 in the studio too. Any insights from having so many vintage axes next to their software imitations?

No question, the emulations are very close. I physically use them differently. The software 2600 would be played from a keyboard, of course, not run off a step sequencer. The real VCS-3 was mainly for treatments [processing other sounds] because any sort of MIDI-to-CV on it is entirely hit or miss, where the plug-in was better at creating actual lines.

Where did the Voyetra-8 show up?

All over. What a synth, as fat as it is unstable! In fact, it’s that bottom end on '[A] Pain I’m Used To.'

What’s the most unexpected thing you did?

Our fair share of electronic treatments to acoustic sounds, but even more of the opposite. For example, Martin might be playing guitar through a synth, but in the next room, we had two or three synths going through different amps, with different mics, to get all these textures we could then blend during mixing. I'd also grab things out of the air with a cheap mic attached right to my laptop, treating them in Ableton Live, which got this washy, distant sound. We created a lot of atmospheres that way.

DM'S TIPS FOR COMPOSING

If you've ever had a great riff in your head that got lost as you were deciding what synth program would sound best, don't feel bad. Even Depeche Mode gets option anxiety, as Gore explains. "We had so many synths in the studio," he says, "and with Pro Tools, enough tracks for all of them. So it's possible to record things 500 different ways and audition each with the click of a button. But that can freeze you." Fletch adds, "You need to force yourself to make a commitment so you don't just go in circles."

"Electronic artists don't have that order that's imposed by having to record drums and bass first, then overdub guitar, and so on," says Ben Hillier, "So it can be harder to be organized. Technology makes it easy to get something halfway there, get frustrated, then drop it and try another musical idea. Don't do that. Get it to what you'd at least call a finished state, even if it's not one you like, then evaluate it in the context of your whole project later.

Ben also recommends analog sequencers, or at least software emulations of them, for getting ideas off the ground. "With a modern MIDI program," he says, "you start from a blank slate. With a step sequencer, you at least begin sounding like something, by virtue of where the knobs are, then change it. But a lot of those random notes sound good, so you keep them."

DM'S WORST GEAR NIGHTMARE

Martin Gore: PPG Wave synthesizers weren't known for reliability, so imagine how shaky a prototype would be. That's what we had in 1982, at this gig in Germany. We learned that Kraftwerk were in the audience, so we were incredibly excited. Of course the PPG malfunctions — catastrophically — and we barely got any sound out of it all night! Imagine your heroes turning up at your show, and one of your main keyboards goes down. That's a nightmare.

WHAT'S IN THEIR CD PLAYERS RIGHT NOW?

Andrew Fletcher: Well, I've actually only had time to go over various edits of the single "Precious". I don't own an iPod. Is it okay to be proud of that?

Martin Gore: I've been listening a great deal to a six-CD set of traditional gospel music called Goodbye Babylon, which is just phenomenal. "John The Revelator" is a heavily re-interpreted old gospel tune about the author of the Book of Revelation, but our lyrical take on it is, "Armageddon? Gee, thanks."

Special thanks to DM webmaster Daniel Barassi (www.bratproductions.com) and Dom Camardella of Sound Design studios in Santa Barbara (www.sound-design.com) for their assistance with this story.