1993-05-xx Keyboard - Depeche Mode

| ||||||||||||||||||

Notes

Alan Wilder discusses the production of Songs Of Faith And Devotion in the May 1993 issue of Keyboard magazine. Scans courtesy of Joe Muscara.

Article

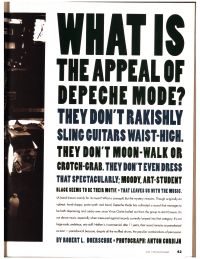

DEPECHE MODE

by Robert L. Doerschuk

What is the appeal of Depeche Mode? They don't rakishly sling guitars waist-high. They don't moon-walk or crotch-grab. They don't even dress that spectacularly; moody, art-student black seems to be their motif. That leaves us with the music. (A band known mainly for its music? What a concept!) But the mystery remains. Though originally an upbeat, hand-clappy, proto-synth rock band, Depeche Mode has cultivated a sound that manages to be both depressing and catchy ever since Vince Clarke bailed out from the group to start Erasure. It's not dance music, especially when measured against records currently lumped into that category. It's not large-scale, ambitious, arty stuff. Neither is it commercial; after 11 years, their sound remains as paradoxical as ever — paradoxical because, despite all the muffled drums, the peculiar combinations of percussion sounds in their drum tracks, the groaning vocals, alternately menacing and vaguely bored, Depeche Mode strikes a chord.

Maybe their endurance has something to do with it. Long after the Human League, Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark, Simple Minds, and the other pioneering synth rock groups sequenced their last synth bleeps, Alan Wilder, Martin Gore, David Gahan, and Andrew Fletcher are still at it. From their first post-Clarke project, Broken Frame, through this year's release, Songs of Faith and Devotion, they've devoted ample time to perfecting whatever it is that defines their style. With U2's longtime producer, Flood, presiding, the Songs sessions added up to eight months of meticulous recording, mixing, and tweaking. As a result, we now have an album on which their sound is — paradox again — more fully developed yet more enigmatic than ever.

For which producer Flood can take a lot of credit. His main clients, the guys in U2, seem to have melted under his direction into a single bloblike noise, from which chiming guitars and desperate singing only occasionally escape. So it is on Songs: You can pick out most of the parts, but the mix encourages you to absorb the music as a whole. "This is the dawning of our love," the key line on the first single, "I Feel You," comes at you as part of a welter of throbbing bass, crashing cymbals, ear-piercing guitar overtones, and squealing general electronica. But while details may have been clearer on some of their previous releases, the sound is still unmistakably theirs.

The crucial element in this sound is Alan Wilder, unabashedly identified in the band's PR as their "musician." Wilder spent more time with Flood than his colleagues doing what he calls the "screwdriver" work. Shortly before flying back to England to rehearse for their tour, which opens during May in Europe and moves to the States late this summer, he took time out to reflect on Songs and ponder the enduring enigma of Depeche Mode.

Do you feel that in terms of sound, Songs of Faith and Devotion differs from previous Depeche Mode albums?

Alan Wilder: It certainly does represent something quite different, which was our objective. We wanted to try and change as many things about our approach to making music as we possibly could, mainly to keep ourselves interested in what we're doing and to challenge ourselves. We were very aware of getting caught in easy routines and becoming bored. I suppose the emphasis is much more on performing on this record. But once that performance was created, we applied all the technology we've come to know and love over the years to put it together in a way that's still uniquely Depeche Mode.

In what respect does performance play a bigger role than usual? Are you sequencing fewer parts?

AW: We still sequence quite a lot of the performance, but we're using the sequencer to restructure what we do. When we just go in and play together, we end up sounding like a pub rock band. That's the problem: We're not capable of going into a room, playing together, and coming up with some magical piece of music. We have to apply all that technology to make it sound more spontaneous and human. One of the things I felt before we started this record was that the last album, good as it was, had a slight rigidity. We wanted to make this record much looser, less programmed. I think we achieved that objective.

What's an example of how the performance element comes through on Songs?

AW: Let's take "I Feel You." All the drums on there are played. Most of them were sampled and then sequenced in the form of drum loops. That's not to say that they don't change as the song goes on. There's a series of loops, which are sequenced together, using [Steinberg] Cubase, in a different structure from how they were originally performed.

In the past, you might have programmed the rhythm without any performance.

AW: Exactly. In this case, we're applying the technology to a performance to make sure that you get all the dynamics of a human performance, all those slight timing changes that make something feel human. On "Walking In My Shoes," for example, there are different loops in the verse, an additional loop comes in on the bridge, and the chorus brings in a complete change of drum sound and rhythm. Plus there are different drum fills, hi-hat patterns, and top percussion parts in each section. The combination of all that gives you the impression of the rhythm changing all the time.

To my ears, many of the parts played by the band sound more obscured on this record than on previous Depeche Mode albums.

AW: Perhaps, to a degree. I would like to think that there's enough clarity within the sound that you can pick out the parts. But I suppose you should always go for a blend. That's what you try to create with your mix. A good mix should stop you from thinking about the mix. If you start analyzing all the details within a mix, you're not really experiencing the music as a whole. To get specific about it, people sometimes mix drums too loudly. Certainly, a lot of dance music is very rhythm-oriented. We place a lot of importance on rhythm as well, but sometimes loud drums aren't warranted. It can be very hard to mix drums quietly, because we're all brainwashed into hearing them right up front. As soon as you mix them quietly, you think it must be wrong.

The changes in the rhythm patterns and the placement of the drums in the mix on "In Your Room" were the most dynamic element in that song.

AW: That song was quite difficult. We recorded the song three or four different ways. One was entirely as you hear it in the second verse, with the smaller drum kit and the "groovy" bass line. But the whole song with that rhythm wasn't strong enough; it didn't go anywhere. We had the song structure from a fairly early stage. We knew where we want-ed the verses, choruses, and middle eights. So much as I did with "I Feel You," I went in and played drums along with the track in one particular style, then did it again in a funkier style, and so on.

The drum sounds themselves seemed to change from one section to the next.

AW: We recorded those drums at a villa we had rented in Madrid. We set up a studio in the basement. The two drum kits, the smaller one and the larger one, were recorded in different spaces, which gave each a different kind of edge. Plus they were played in very different ways. The smaller drum kit, which comes in during the second verse, has quite an interesting loop going around it; it's another drum kit that's reduced by being put through a synthesizer and then distorted. That turns it into weird percussion sound, which is then looped to offset against the real drums and form an unusually funky groove. We often do things like that. We'll record a drum kit fairly straightforwardly, balance it together, and put the whole thing through a synthesizer. At the beginning of "I Feel You," for example, the drum kit is played, sampled, put through a synth, distorted, and then reduced to half-level.

What kind of synth would you typically use on drum sounds?

AW: It could be anything. We've used a Roland 700 modular system. We've also used distortion boxes, filter sections. Often we use guitar effects processors. We're quite fond of the Zoom; it has great distortion and compression effects.

At the height of the crescendo in "In Your Room," we get the line, "Your eyes cause flames to arise." That's the one part of the album where you underscored a single word, with a cymbal roll behind "flames."

AW: That was a late addition. Since that's such an up part of the song, it felt necessary to add something at that point. We put it in at the mix. It's often not until you get to the mix stage that it becomes obvious that another part is required. When you're in the recording process, you've never got it sounding good enough to tell. So quite a few of those embellishments get put on at the mix stage, like backwards cymbals.

What attracts you to reversed sounds? There are plenty of them on this record, and on previous Depeche Mode albums too.

Keyboard - May 1993

AW: I'm not quite sure, but I'm nearly always the one who suggests those sounds, so it must have something to do with me. I suppose it's the strange psychedelic effect. Having taken psychedelic drugs in my youth, it reminds me of listening to music in that state of mind: Everything sounds backwards. So when I hear something backwards, it takes me off into a sort of trippy mood. You can also use backwards sounds to lead from one section to another, or form weird fills from a verse into a chorus.

There's a backwards episode at the end of "Mercy."

AW: That's a backwards high piano. And the beginning of "Judas" has Uillean pipes recorded straight, with backwards reverb mixed in. The nice thing about backwards reverb is that it adds space to a sound without making it washy. I'm against using a lot of reverb most of the time, because I can't stand the distancing effect it makes. But I do often want to hear sounds in a space, or try to keep all the clarity of a sound while still trying to put it somewhere. Backwards reverb can do exactly that. There's a part in the middle of "Rush," the sort of progressive rock track near the end of the album, where the voice has lots of backwards reverb; that really sets the vocal part off.

Do you also subject your piano sounds to a lot of processing?

AW: Quite often we do. The piano part at the beginning of "Walking in My Shoes" was put through a guitar processor, which distorted it and made it more edgy. We added a harpsichord sample on top of that. And on "Condemnation," we put the piano through some kind of a wobbly pitch-shifter. The idea of that track was to enhance the gospel feel that the song originally had without going into pastiche, and to try to create the effect of it being played in a room, in a space. So we began by getting all four members of the group to do one thing each in the same space. Fletcher was bashing a flight case with a pole, Flood and Dave were clapping, I was playing a drum, and Martin was playing an organ. We listened back to it. It was embryonic, but it gave us an idea for a direction.

There's a lot of guitar on this album, but it's never played in a cliched, blues/metal style. It seems as if the kinds of samples and synth sounds you use dictate just how you can use it.

AW: We have a very strong aversion to typical rock guitar playing. Something has to be said about the intensity that rock records have, but we would like to recreate that intensity in our own way, without resorting to those tactics. The idea of a high, screaming guitar part might translate into radio frequency waves, for example. Our guitar parts, on the other hand, tend to go quite weird. We run them through Leslies and other devices that make them less and less guitar-like while still keeping some of the power of the instrument.

Have you added much new equipment since the last album?

AW: Not really. The only change is that we're using more acoustic instruments, especially for writing. When we're working out songs together, we usually play guitar, piano, bass and drums. They're the most fun instruments to play, really. Each one is so dynamically pleasing. The only problem is that the sound of the piano can sometimes dictate what you write. It seems to be helpful to compose on instruments that give you lots of dynamic response. But then we'll transfer what we've written to a sound that's completely different and the riff takes on a new quality.

Your electronic setup hasn't changed much in recent years?

AW: We've still got the same selection of samplers — Akais and [E-mu] Emulators. And lots of rack-mounted and modular synths: a Minimoog, Oberheims, the Roland 700 system, ARP 2600s. There are fewer modern synthesizers than ever before — no DX7s, PPGs, or things like that.

Is it a question of sound or limited programmability that steers you away from newer gear?

AW: It's sound. If we felt that the DX7 had great sounds, we'd use it all the time. The older synthesizers have an organic quality, a roundness and grittiness, that you just don't hear on digital things. But the flexibility is important too. You've got so much flexibility of routing the sound on the older gear; you can create your own patches without adapting somebody's factory sample. The DX7 did initially impress me, because it had bell-like sounds that weren't readily available at that time. But you were fucked if you wanted to change those sounds, unless you had a very thorough understanding of algorithms. Nobody I know could get their head 'round that. I certainly couldn't.

As a member of Depeche Mode, you've got an inside perspective in assessing the impact of electronic technology on pop music over this past decade. How do you feel about how bands typically use this equipment?

AW: I'm mainly disappointed. It's a shame to see electronics really being utilized only in the dance area. But, you know, though we're cited as being so instrumental in developing electronic dance music, we're trying to move as far away from that as we can. That's purely because the emphasis of what we do is on songs. Everything has to enhance the song, to create the right atmosphere. I do love dance music and Kraftwerk and techno; you're always going to see that side of us come through. But you've got to apply it to the song. And sometimes rigid electronics don't apply to songs that are more warm and emotional.

What do you think about changing tastes in synthesizer sound?

AW: There's good and bad. A lot of people in rap music are using the technology in an interesting way to make their records sound dirty. So much of pop music is so clean and pristine, and there's an awful lot of bollocks because of it. I like to try and capture both sounds, to make it clear, with a full frequency range across the board, but also to have a lot of grit. Take "Mercy," for example. We were going for this rap-like drum loop. If you listen to that track with just the rhythm and one or two other elements going, it sounds fuckin' great. You can whack out all kinds of low-end distortion on the bass drum. But as soon as you start introducing other instruments over the top, it begins to sound wooly and waffly down in the low end, and you've got to start compromising your rhythm sounds in order to fit on all the other parts. As soon as you do that, you can start to lose all the drive. That was really a difficult song to mix.

Do you intentionally use low-bit samplers to maintain a grunge element in your sounds?

AW: There's definitely something to be said for that. The first Emulator sounds great because it's such a bad quality. It's the same with analog tape; that hiss can be brilliant.

What sampler do you use for your drum sounds?

AW: Generally the Akai S1100, not so much for its sound quality, which is fine, but because it triggers much tighter than the Emulator. And the way it assigns outputs has so many advantages over the Emulator, although I think the sound of the Emulator is slightly better.

What keyboard will you be using onstage in the tour?

AW: Possibly the [E-mu] Emaxes, because they're convenient and roadworthy. It would be useful to have something that has an extra octave on it, though, because we have to as-sign so many sounds across the keyboard for each song.

Will you carry any extra musicians?

AW: Possibly, perhaps singers. All I know is that I'm going to be playing some live drums, and Martin will almost certainly be playing more guitar. I suppose we'll be leaning more toward being a "rock band," but I certainly hope we won't be creating that general effect.

FOR FURTHER READING Members of Depeche Mode were previously interviewed in the June '82 and Oct. '86 issues of Keyboard.