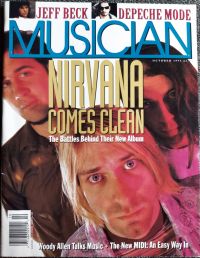

1993-10-xx Musician - Depeche Mode

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

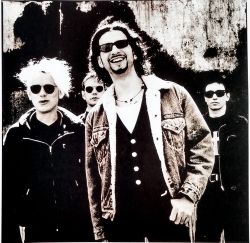

Andrew Fletcher, Martin Gore, Alan Wilder, and Dave Gahan discuss the workflow behind the songwriting and production of Songs Of Faith And Devotion and the 1993 Devotional tour in the October 1993 issue of Musician magazine.

Article

DEPECHE MODE - MOPE NOW PARTY LATER

by Jon Porales

It's quarter to three in Barcelona; the night is young. A few hours earlier, Depeche Mode performed at the Saint Jordi sports palace, a shiny new arena built for the 1992 Olympics. As somber, penitential images floated above him on video screens, Dave Gahan crooned and intoned Martin Gore's lyrics about fear, longing, obsession. "Death," he proclaimed to the arena full of black-clad, undulating Spanish youth, "is everywhere."

Where is Gore now? Could he be in some hermit's cell, contemplating the fate of mankind, brooding over mortality? Could he be in some private retreat, offering himself to someone as "Your favorite passion/Your favorite game/Your favorite mirror/Your favorite slave"?

Well, no. Actually, he is at Barcelona's Studio 54, a blatant copy of the long-gone New York disco, where he has been holding court on the VIP balcony as techno music pounds away and lasers trance phantom tunnels in the air. And at this precise moment, Martin Gore, idol to brooding youth everywhere, is limbo-dancing backwards between the legs of a backup singer, a broad grin on his face. The band may not have recorded a fast song, or a light-hearted one, in years. But nobody mopes full-time.

Depeche Mode has turned itself inside out during its 12-year career. It started out as a standard English rock story: students trying music as a lark. Gore and Andy Fletcher played guitars; Vince Clarke played synthesizer and soon Dave Gahan joined as singer. Notions of pop disposability were featured on the art-school curriculum; Depeche Mode, a name plucked out of a French magazine, meant "fast fashion."

In the heady days of post-punk, the new technology of synthesizers and drum machines looked like perfect toys for musical amateurs. Soon, all three instrumentalists had switched to keyboards. Clarke, then the group's main songwriter, came up with percolating songs like "Dreaming Of Me" and "Just Can't Get Enough", a Top 10 British single. In 1981, the group released its first album, Speak and Spell.

But after that album, Clarke quit Depeche Mode. Alan Wilder, another keyboardist, joined the group and Gore quietly picked up the songwriting franchise. While Clarke grew campier and campier leading Yazoo (Yaz in America) and then Erasure, Gore's songs turned increasingly plaintive, exploring murkier emotional zones: the dominance and submission of "Master And Servant", the desperation of "Fly On The Windscreen", the heresy of "Personal Jesus", the obsessive desire of "Rush".

And the group that had expected to be disposable inexorably became an institution: filling arenas, selling millions of albums (Violator, released in 1990, sold 5 million copies worldwide, and the 1993 Songs Of Faith And Devotion has sold 3 million and counting), even touching off a window-smashing stampede when thousands of fans descended on a Los Angeles record store for what should have been a simple autographing session.

"Our career has been a dream career," says Fletcher. "It's been a gradual rise up, without too many down periods, so we haven't been through a real crisis. You can say our first record was a bit naive, our second record wasn't very good, we've made some embarrassing videos and there are some embarrassing photos around. But I wouldn't change anything."

Songs of Faith and Devotion, and the tour that comes to the United States this fall, do mark a change for Depeche Mode. From Speak and Spell to Violator, the band's trajectory was inward, away from the dance floor and into the private space of ballads made for headphones. The sound of four musicians playing together melted into eerie, sustained counterpoint, with quiet and ominous tones ticking away behind organ-like synthesizers; the music grew hermetic, with few discernibly natural sounds beyond Gahan's voice.

Songs takes a different tack, using more live sounds. "One Caress" was made with a string section, and was finished in three hours of takes rather than three days of tinkering and sequencing. "We felt that what was lacking in our music was that we were still sounding quite mechanical," Fletcher says. "We wanted to loosen up a bit. And our producer, Flood, was going on and on, trying to get us less narrow-minded, turning the screw all the time till we said, 'Yes, let's give it a go."

On the current tour, the band's shift gets acted out spatially. For the first hour of the show, Gahan has the stage's lower level to himself while the other three band members look down on him from their keyboards. "They're more separate from me than they've ever been before," Gahan says. He works hard, defying the songs' earnestness to shake his hips and hair like a Bono wannabe. "I love to be a showman – that's obvious," Gahan says. "I come off it as high as a kite."

Gradually, one by one, the other band members join him: Gore with a guitar, Fletcher on a second keyboard and Wilder settled behind a drum kit, where he socks out the beat of "I Feel You". It's as if Depeche Mode has descended from the ether to the earth.

For the moment, Depeche Mode is sequestered. Although the warm Barcelona sun pours down benevolently outside, the band is holed up in its hotel attending to business, recording radio station IDs and submitting to interviews. Across the street a dozen teenagers, in the inevitable black, watch the hotel doors intently, patiently awaiting the appearance of a band member and thus, ironically, deterring any casual exits.

But it doesn't take too much convincing to pry Gore out of the hotel for a stroll, accompanied by a genial bodyguard. Only one eager teenager dares approach, asking an unperturbed Gore to autograph a CD for "José," on the way to Barcelona's somber Gothic cathedral – just the place for a songwriter so concerned with belief, truth, transcendence and redemption. "I think I'm probably obsessive in those areas," he says with the hint of a smile. "I probably think about it too much. But I've never belonged to or followed any church or anything at all. I think there's just something inbred in me.

I don't condone Christianity in any way. I'm in a lot of ways very anti-organized religion. I just think that those symbols are handy and are there for me to use in a very different way. The songs are often not about plain religion. They're more about love and sex and religion all tied into one. For me, love and sex are like a religion."

Is this blasphemy? "I do believe there must be some form of higher being," Gore says. "Otherwise I find the whole meaning of life very futile. I just hate the way that man twists religion, twists this higher being. I am fascinated by religion, and I've always liked the idea of faith. Whenever I write a song, that just naturally comes out. But because I can't really comprehend this higher being I believe in totally, I have to find that faith somewhere else."

One touchstone is the craft of songwriting. Gore, according to Fletcher, is familiar with "every song known to mankind." "Music is the only thing that's ever really interested me," Gore says. "A lot of people get into films, but I go out to cinema only once or twice a year. I can't feel the same enthusiasm for anything other than music."

While Gore seems to keep up with everything, Depeche Mode's music is a world away from the speed and aggression of most current pop. "Even as a young kid," he says, "on every album I bought, the slow track was my favorite. I find it hard to write fast songs these days. Somehow they don't create the right sort of emotion for the words I'm writing. The songs are realistic, and love isn't always the smooth ride that it's made out to be. I find it also really boring to write happy love songs. Yet a lot of the songs end on an optimistic note, even if they start off bleakly. And I find that the realism is optimistic. I think a lot of people miss that point, and I think that's why we get wrongly accused of being doomy."

Gore, who is 32 years old, started out as a child of 1970s pop. "The first music that I really got into seriously, when I was 12 or 13, was Gary Glitter. As un-serious as that may sound, Glitter and [Mike Leander] wrote great pop songs. As I got older, I got into people like Neil Young, John Lennon and Leonard Cohen, and I used to really like Jonathan Richman at one point. I think Neil Young feels every word he writes."

Is it the same for his own songs? "Yes, yes, yes," he says. "That's why I think I'm not very prolific at all. I don't understand how people can churn out song after song and mean every word, and for every one of the songs to be important."

It's easy to read gay or bisexual meanings into some of Gore's songs, like "Never Let Me Down Again", which ruminates, "I'm safe as houses/As long as I remember who's wearing the trousers." Gore, who has a longtime girlfriend and a child, rules nothing out in the songs. "I've always liked the idea of the songs being ambiguous," he says. "It really doesn't mean very much to me if people think I'm gay or I'm straight. I've always really detested the macho image in rock music. At some points I think I probably took it too far. When I used to wear skirts onstage and things like that, I think it made the band suffer. We're still not respected in a lot of circles, and a lot of it is down to that image. But when I look back at it, it still makes me laugh.

"When I write songs, I try to move people," he says. "It's as simple as that. I don't have any great master plan, to shake up the world. All I want to do is capture passion with words and music."

With Gore's songwriting at its core, Depeche Mode is a highly efficient organism; each responsibility has been neatly delegated. Gore writes the songs, Wilder arranges them, Gahan sings them and Fletcher takes care of business. Visuals have been handed over to Anton Corbijn, the photographer and video director; he designed the band's current stage show and is making a video documentary of the tour. Flood, who has also worked with U2 and Nitzer Ebb, co-produced Violator and Songs of Faith and Devotion with the band.

Depeche Mode doesn't have a manager. "The primary purpose of a manager is to give you some clout, to get a contract, to be someone with influence," Fletcher says. "We managed to do without, and we never took one on." Fletcher also reveals that until its latest album, Depeche Mode's contract with Mute Records was a handshake; now, it's a simple one-album deal.

Before joining Depeche Mode, Fletcher worked as a pensions quotations clerk, crunching investment numbers. With the band, he says, "My whole life is dealing with numbers." He doesn't mind.

"I don't find it very stimulating making music," he says. "I'm a useless musician. When I played bass, I never had any ambitions to be a great bass player, and when I took up keyboards, I never had any ambitions to be a great keyboard player.”

"I don't really find music that stimulating. I do listen to it, and it's been such a part of my life the last 10, 12 years, but I find I get more pleasure from other things. With the band, I still find the whole job challenging and rewarding, the fact of creating something and releasing it, the marketing, the promotion side of things. That's quite interesting, selling our products." The product itself, however, isn't a simple business proposition; it evolves from teamwork. Melodies, harmonies and lyrics are on the demos that Gore makes in his home studio.

"From Violator onwards," Gore says, "the others asked me to keep demos as simple as I possibly could, so that we didn't get too many preconceived ideas, and so that the songs were open to all kinds of possible interpretations before we got to a studio. Sometimes I've kept the demos as simple as an organ pad and the vocal, and then we've tried out different approaches in the studio. With every record it gets more and more difficult, because we have to experiment more and more to come up with something new that we haven't tried before."

"It's a long, painful process, I can assure you," says Alan Wilder. "It's a lot of trial and error, mostly error. We've discovered that the best way to work is to get those that have a low boredom threshold, which is everyone apart from me, to throw ideas at a song really quickly. Then myself and Flood will take those ideas, adding any ideas we have, and refine them to the point that they start to work for us. Which can be a very long process of sampling, bits of performance, whatever.”

"On this last record, our approach was to try and perform as much as we humanly could. Drum things, guitar bits and pieces, anything that we could perform we would. If we try and perform a whole song together as a band we sound like pub-rock, so we've realized that we have to apply the technology to that performance. But to try and keep all the spontaneity, we'll sample bits of it and restructure it in a more interesting way, rather than program stuff so much. Which can then spark off different ideas."

Gahan takes the demo for private vocal study. "The first thing I do is, I'll be really nervous and I probably won't play it for a couple of days. Then, I listen to the lyrics first, before I listen to the melody. And then I try and interpret what I think Martin's feeling, but then I also like to be able to feel whatever I want to feel too, and try to marry the two. It's a bit schizophrenic."

The band struggles with arrangements. In the reject pile there is a near-reggae version of "Judas", while "In Your Room" went through three incarnations – an austere ballad, a kind of soul groove and a rock anthem – before the band decided to use a little of each in the finished version.

Twitching and glimmering in the background of Depeche Mode songs are strange noises, perhaps a highly tweaked sample of a choir from an Ennio Morricone soundtrack or a mixture of backwards and forwards piano sounds. "We're looking for different ways to approach sounds than everybody else," Wilder says. "We try and find unlikely sources. A typical sound for us would be to get something going on a synthesizer, put it through a guitar effect, sample it off, create an interesting loop.

"If we want a drum sound, we'll record an entire drum kit in a space and put that through a synthesizer, distort it, compress the fuck out of it, and you might end up using that drum kit as a small percussion part rather than a drum kit. Sometimes we might go around in circles and up our own arse, but we try not to."

One trick he reveals was used, not for the first time, in "The Mercy In You". For the bridge, Gahan learned the lyrics backwards, phonetically, and sang them over a mirror image of the melody; the tape was then reversed, lending a ghostly tone to the vocal.

For stage versions of the songs, Wilder essentially does dub remixes. He goes back into the studio to remove parts that will be played live onstage and shift arrangements for maximum impact in concert. And the band doesn't mind if many of the details on those digital tapes are lost in the roar and jubilation of concert crowds.

"The record achieves one thing," says Gore, "and the concert achieves something totally different, which is always like a celebration to me. Although the songs are very intimate, and that gets lost when there are 20,000 people there, I think there is a bond that all the fans feel."

Obviously, the T-shirted crowd at the hotel door wants to feel something a little closer. "Sometimes signing autographs and having screaming kids is a bind," Fletcher says, with a modest grimace. "But the day they're not there is the day you're doing something wrong."

GEAR A LA MODE

Depeche Mode keeps things simple onstage: no amplifiers. Every sound, from keyboards to guitar to drums, runs through the P.A. system: a Brittania Pow Flashlight System. Dave Gahan and the backup singers use Samson Synth radio microphones with EU 757 capsules.

Martin Gore plays a Roland A-50 and Alan Wilder plays an Akai MX1000, each controlling two Emulator Emax II samplers: Andrew Fletcher has another pair of Emaxes. Each pair is hooked up in parallel, so that if one were to malfunction, the other is ready. But "I don't remember an instance when we had to go to a spare," says Wob Roberts, the keyboard technician. Samples come from strange and sundry sources, including old analog equipment.

The piano onstage is a Korg 01/W Pro X transplanted into a grand-piano body. For down-stage keyboards, Fletcher and Wilder use Philip Reese MIDI line drivers. A MicroLynx sends SMPTE time code to the video and film setups.

Away from the keyboards, Gore plays either a Gretsch Country Gentleman or a copy of a Gretsch Anniversary guitar, strung with Gibson strings, from .010 to .046 gauge. Dick Knight copied Gore's original Gretsch for stage use, using Gretsch parts but adding more wood in the body to cut down feedback. The guitars run through a MESA/Boogie Tri-Axis preamp and a Zoom 9002 effects processor, with a Sennheiser UHF transmitter.

Wilder's drums are mostly Yamahas: a 22" bass drum and 12", 13", 14" and 16" tom-toms. He uses Noble and Cooley piccolo and 7" snare drums and Zildjian K cymbals: a 22" ride, an 18" China, 16" and 18" crashes, a 6" splash and 13" hi-hats.

And don't forget the tapes: two Sony 3324s, one of them a spare. Of the 24 tracks, Depeche Mode uses only 14, because many of the songs were dubbed from a 16-track Tascam that used 12 tracks for sound and four for sync. "As soon as anyone sees the size of the machines, they think the whole show is on tape," says Roberts. "But it's just bass and drum parts and a couple of sequences. This band does not mime."